For the last decade, you’ve probably seen photos of and photos taken by our research associate, photographer and social media wiz Bethany Augliere. Now’s your chance to learn a little bit more about her!

Bethany grew up in the suburbs of Washington D.C., but always had a passion for the ocean, nature and adventure. She spent her summers bodysurfing waves with her grandmother at Jones Beach on Long Island, New York, exploring tide pools with her grandfather and snorkeling the gin-clear waters of the Florida Keys with her parents. At just eight-years-old she went scuba diving with her dad and a professional instructor in the Florida Keys, and always had an affinity for underwater breath-holding competitions with anyone who would challenge her (something her mom did not particularly enjoy)!

Scuba diving at 8-years-old in the Florida Keys

Challenging her older cousin to a breath-holding competition at a little over 2 years old.

When it came time for college, she decided to study wildlife science at Virginia Tech. She participated in undergraduate research examining movement patterns and habitat use of black bears. During the summer, she interned at Mote Marine Laboratory to help with husbandry and research on the hearing abilities of two manatees, Hugh and Buffett, and also spent two weeks volunteering with the Sarasota Dolphin Research Program. As an undergraduate, she studied abroad in both South Africa and Ecuador, which included a trip to the Galapagos Islands.

Bethany working as a research intern at Mote Marine Laboratory in Florida.

After graduating college, Bethany worked as a biological technician for the Protected Resources Division of the National Marine Fisheries Service, where she assisted on a range of projects from seagrass to dolphins, as well as assisting with the Marine Mammal Stranding Program. When her contract expired, she moved to the Florida Keys to work as a divemaster and lead guided kayak eco-tours at John Pennekamp State Park. During that time, she was searching for graduate programs and came across the work of Dr. Denise Herzing. She met with Denise and it seemed like a good fit.

In 2009, Bethany Augliere joined the Wild Dolphin Project as a graduate student at Florida Atlantic University with Dr. Denise Herzing as her advisor. Her research focused on the habitat use and movement patterns of spotted dolphins in the Bahamas and she earned her master’s degree in 2012.

Now, Bethany Augliere continues to work with the project to lead trips, document the research, run social media and blogs, and collaborate on research projects. Outside of her work with WDP, she continues to work as a biologist, but also works as a freelance science communicator and conservation photographer and has published work in outlets such as National Geographic and Oceanographic Magazine. She recently produced a children’s documentary on threatened gopher tortoises in Florida with Schoolyard Films, led by Emmy-award winning filmmaker Tom Fitz.

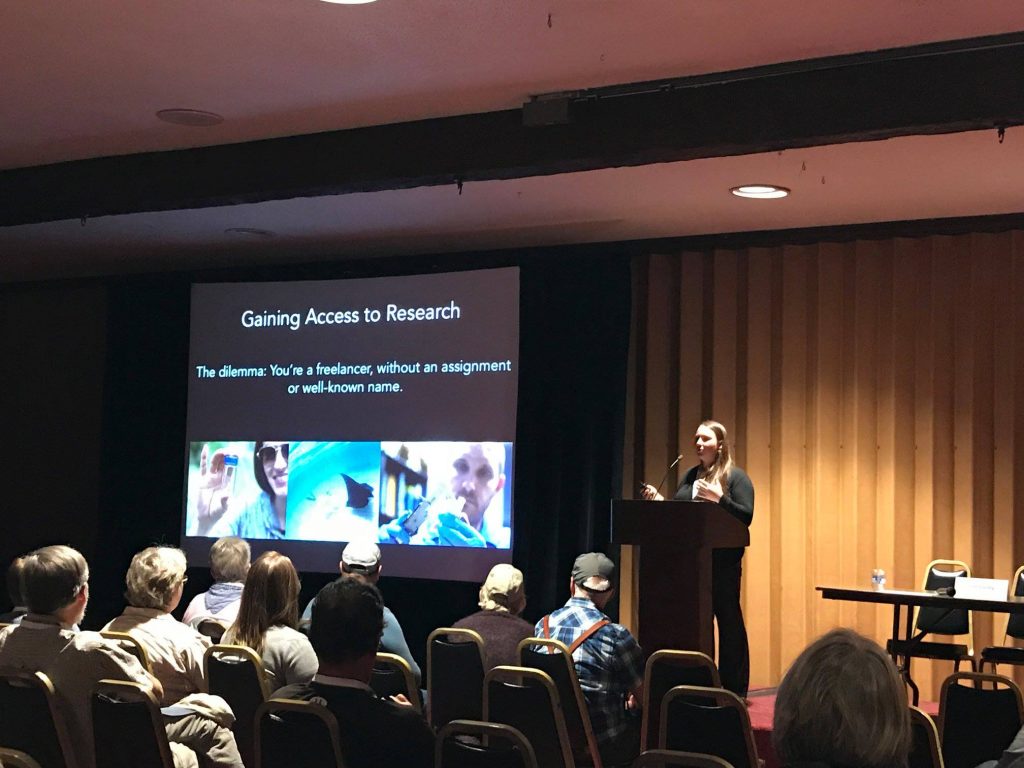

Bethany giving a talk at the 2018 NANPA Nature Photography Celebration about conservation photography.

WDP: Do you have a favorite dolphin encounter or memorable experience from the field?

BA: There are so many to choose from, having been with the project for more than a decade. I’m always grateful to be out on the water, connected to sea, for every sunrise and sunset and honestly, for every encounter with the dolphins because every experience is unique. However, I think one of my most memorable experiences was with Nassau and her new calf at the time, Nautilus. It was one of those perfect, glassy days without a lick of wind. We found dolphins and slipped into the water to document their behavior. Everything about the experience just had this calm vibe. Nassau began slowly circling the group with her calf right next to her. Denise has known Nassau since she was a calf in the 90s, and it felt as if she was introducing us to her new youngster. I remember feeling awe-struck that this wild animal trusted us enough to be around her new baby.

Bethany’s photo from the experience of Nassau showing off her new calf Nautilus.

I can think of a few other less pleasant memorable experiences too! One time, it was the end of the field season and we still hadn’t seen Paint, a dolphin Denise had also known for years. It was really rough and choppy conditions with six-foot seas. Of course, we ended up finding dolphins and Denise was eager to see who was in the group, especially because we both thought we saw Paint from the surface (she had a very large but subtle scar). I eagerly jumped in the water. As the dolphins surfed the waves around me, I spun circles trying to film them with the video camera. I was getting sloshed around in the waves and started to feel queasy looking through the viewfinder. Sure enough, nausea got the best of me and I vomited in the water. But, I didn’t let that stop me. I turned my head to yak behind me, and kept filming!

WDP: As someone with a scientific background, what led to your work as a photographer and science communicator?

BA: It’s a long and winding path! As an undergraduate student back in 2003, I first had disposable cameras, then a little point-and-shoot camera that I used to bring with me on hikes and when out exploring, and during my internships. I always enjoyed documenting my experiences, and a lot of that included science and nature. I also moved around a lot when I was younger, so going out and taking photos was a way I explored these new places and learned the wildlife. I would take photos of birds I didn’t know so I could identify them later. Wanting to become a better photographer just became this natural progression the more I did it, and the more I traveled.

Bethany’s first attempt at science communication (before she knew that’s what she was even doing) as an undergraduate student at Virginia Tech, documenting her work on a black bear reproductive study.

My time with the Wild Dolphin Project ignited my interest in science communication. Habituated to human presence, these dolphins have granted me access to the most intimate moments in their lives, such as observing calves learn to swim and hunt, watching mothers nurse their young and glimpsing males fight for the attention of coy females. I’ve spent so much time among the dolphins and began to know them as individuals. I knew that Venus enjoyed playing games with seaweed, that Brat was always getting into trouble with his mom, or that Nassau survived a shark attack. I’ve also seen them playing with plastic and leave their home of 30 years due to changing oceanographic conditions. Watching their relationships and struggles, some of which due to human activity, ultimately led to my interest in storytelling and conservation photography. I wanted others to know their stories and hoped, that if people could connect to these wild animals as individuals, they might be inspired to care about and protect them. Now, I don’t want to just document the dolphins, but also the incredible scientists, conservationists, and what they are doing to understand more about these animals and protect them.

WDP: How do you become a science writer or photographer?

BA: As far as the photography and science communication work, there are so many paths. A lot of scientists use their own social media platforms to document their science and share it with followers. Both Twitter and Instagram are popular places for scientists. Some of these people write articles about their work in magazines like Scientific American, or diving magazines. Initially, I started a blog during graduate school at FAU writing about local wildlife I photographed.

If you want to do science writing beyond your own science, then I suggest reading outlets that interest you to see what kind of stuff they write about — new studies, features, profiles of scientists etc…For conservation photography, find something in your “backyard” to document. You don’t need to travel to exotic locations to be a photographer. My most recent story in National Geographic came from photographing manta rays that live right next to shore and working with a scientist that’s studying them. Once you have images or a story idea, you can pitch that to an editor. You’ll get lots of rejections in this field, so be ready for that. You also don’t have to pitch for the biggest outlets right away, you can start with smaller, local publications.

Lastly, education never hurts. Eventually, I realized I wanted formal training and went to graduate school for science communication at UC Santa Cruz. I learned all about pitching editors, writing news etc…I can’t recommend that program enough!

Me photographing a manta ray in South Florida for one of my conservation photography projects.

WDP: You wear a lot of hats with the WDP, are you working on any research now?

BA: Yes! For the Wild Dolphin Project, Denise and I, along with her research assistant Cassie Volker-Rusche, are actually working on a paper to describe an interaction between two species of dolphins in Florida, that’s never been seen or documented before in Florida — to our knowledge. Outside of WDP, I’ve got some exciting research I’m assisting with on leopard seals in New Zealand too.

WDP: What’s one thing that’s surprised you since working with wild dolphins?

BA: When I first came to the WDP, I was enamored with the idea that wild animals wanted to interact with people. It was truly fascinating to play with wild dolphins, because they chose to and I will never take those experiences for granted. However, with time, I actually became less interested in the interactions and more intrigued watching dolphins be dolphins — watching them interact with each other, observing young males develop their alliances, witnessing juvenile females become mothers. Their lives are fascinating and complex and it’s a privilege to learn more about them.

A group of juvenile males court a female, named Mila. Photo by Bethany Augliere.

WDP: What advice do you have for a younger student interested in becoming a biologist?

BA: As a scientist, it’s initially a pretty straightforward path. Get a college degree in a field you are interested in, and while doing that, find work, volunteer, and research experiences because you never know what will pique your interest, and what connections you will make that could lead to further opportunities. I worked in a lab counting spinal malformations of tadpoles and realized I had no interest in working behind a microscope. To me, understanding the kind of science and questions that interests you is more important than the species. Do you like genetics, physiology, behavior, ecology etc…?

WDP: What’s one thing you’ve learned from your time with WDP over the years you would want people to know?

BA: Our job as researchers is to passively observe the dolphins without disrupting their natural behaviors. If they choose to interact with us, that is on them. Whether it’s as a scientist or photographer, I want to minimize my impact on the animals. These animals live close to humans and face daily disruptions from boats, other people jumping in with them, noise pollution, etc… I don’t want to add to their problems to get a photo just for social media. So, for anyone who is watching or photographing animals, I would just remind them to be respectful and keep your distance, because you never know what behavior you could be impacting, such as feeding or nursing. Also, in the U.S. it is actually illegal to approach marine mammals within a certain distance.

A bottlenose dolphin feeding in the sand. Photograph by Bethany Augliere while freediving.

WDP: How do you balance family life with a young child and work?

BA: First, I never wanted work to be the reason I didn’t have a family. I knew it could potentially come with sacrifices, but I was willing to make those sacrifices. Secondly, I view my work as more of a lifestyle and I incorporate a young child into that lifestyle. I have the privilege of having a flexible schedule because of the nature of my freelance and contract work. It’s not easy but it’s worth it, and it does require more planning. I often work very early mornings and late at night. Having a child also means my time is even more precious than before. When I’m working — I’m working, which means I’ve actually learned to become more efficient and not waste time. That has helped me understand and value my worth and skills (which has helped when it comes to negotiating rates and fees) and it means I’m choosier about the projects I take on. When I’m with my child, I’m with him and engaged with him and we are typically outside, exploring nature. When possible, I even bring him in the field with me. Like I said, it’s hard but if you want it to work, you just make it work. Having a supportive partner and family helps with that too, and of course, the pandemic has sort of changed everything.

For the record, I continued to work in the field and photograph dolphins, sharks , sea turtles and manta rays while pregnant!

Bethany photographing a leatherback hatchling sea turtle, while four months pregnant. Photo by Nicodemo Ientile.

You can find Bethany on social media to follow more of her work or go to her website, for a list of her published work and photo galleries.