Little is known about the harbor porpoise, including their social structure. That’s why Cindy Elliser, Ph.D., research director and founder of Pacific Mammal Foundation (PacMam), launched a research project in 2014 to study this small coastal species off Fidalgo Island in Washington State. She recently published the first 3 years of their research in the journal Marine Mammal Science.

“Porpoises in general are less well studied than most dolphin species. I like to say where we were 30-40 years ago with dolphins is where we are now for many porpoise species,” Cindy said. “We know surprisingly little about their behavior, ecology, movement patterns, and social and population structure. To be able to be at the forefront of discovering new information about such a poorly understood species is very exciting.”

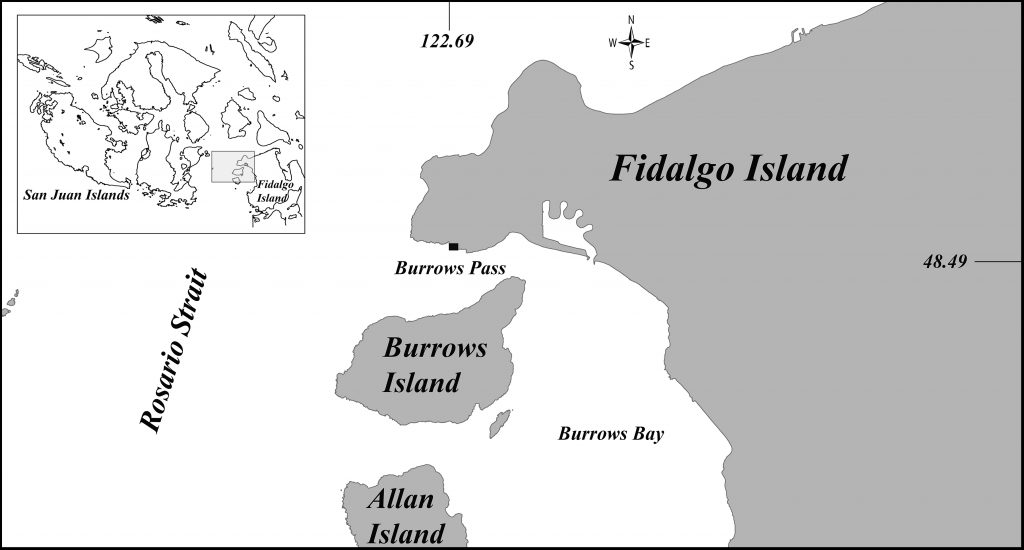

A map of Cindy Elliser’s, Ph.D., study site to study harbor porpoise in the Pacific NW.

The harbor porpoise is a small, shy marine mammal usually seen in groups of two or three. They are one of eight living species of porpoise. (What’s the difference between a porpoise and a dolphin — read here).

Two harbor porpoises in the Salish Sea. Photo Credit: PacMam, CIndy Elliser, Ph.D.

Their small size and uniform color also makes it difficult to track individuals — unlike the spotted dolphin we study in the Bahamas, which have lots of spots or the bottlenose dolphins with their large fins that acquire nicks and notches with age, making it easier to identify individuals.

Cindy spent 10 years with the Wild Dolphin Project as a research assistant and doctoral student advised by WDP director and founder, Denise Herzing, Ph.D. So, she had plenty of experience with photo-ID of marine mammals before she started her work with the harbor porpoise. During her time, she was the resident expert on identifying the bottlenose dolphins, which are generally more difficult to ID than the spotteds.

“Photographing bottlenose dolphins was often difficult, they were a bit more shy than the spotted dolphins and getting a good photograph could often be challenging. However, I never thought I would look back on those days as being relatively easy – the difficulty associated with photographing harbor porpoises is on a whole other level. Little did I know that my days with the bottlenose dolphins in the Bahamas would help prepare me for days with harbor porpoises in the Pacific Northwest,” she said.

Here’s what Cindy had to say about starting PacMam and studying harbor porpoises in the Salish Sea.

Knowing that it is hard to track harbor porpoise as individuals, how did you prepare and handle that? What are some of the things you used to identify them?

CE: Honestly, I had no idea what I was getting into! I didn’t even know if we could do it. I just wondered, is it possible? Is there a reason that no one has really done it long-term, or is it just another artifact of the species not being the focus of much research overall?

The only way to find that out was by trying. So I got a big zoom lens for my camera and started taking pictures to see if 1. We could get usable pictures in the first place, and 2. If they were usable, did the animals have stable markings that we could use to identify them. After LOTS of photographs (yeah digital photography!), with many, many not being usable, it was clear that they did have markings that were stable over time. That’s when myself and my assistant sat down to describe what we saw.

Cindy Elliser, Ph.D, takes photos — using a very long zoom lens – to try and photo-ID the small harbor porpoises.

For most small cetaceans nicks and notches in the dorsal fin are used for photo-ID, but harbor porpoises with their small fins don’t really have too much of that. So we looked elsewhere. My time underwater with the bottlenose dolphins in the Bahamas showed me that pigmentation patterns on the animals could be used for ID – there were small markings on the sides of the animals that were unique, but not discussed in the literature as usable for ID (likely because most people were not photographing bottlenose dolphins from underwater).

We ID’d porpoises primarily by the pigmentation patterns along their side (where the lighter belly meets the dark dorsal side), that in stranded porpoises have been documented as individually distinctive, but no one had tried yet for photo-ID. We also use scarring patterns on the body, as unfortunately for them, many individuals have distinctive scars (from what we don’t know). But since these animals are harder to ID than other species, we want to make sure we are correctly IDing the individual. So we also use other marks like nicks and notches in the dorsal fin, when available, and peduncle (tail area) and confirmation marks relating to dorsal fin size and shape. This helps to reduce misidentifications, as two animals might have a similar ID feature, like pigmentation, but are not likely to also have the same scar and/or dorsal fin size and shape.

Was the process of identifying them easier or harder than you expected?

CE: That is a good question – to some degree, I assumed that since no one had done it yet and there were so many other species that use photo-ID , even painted crayfish, that it likely wasn’t doable. That was the reason. But, that was an important lesson to learn – just because something hasn’t been done, doesn’t mean it isn’t possible. It was just that no one had taken the time to see if it could be done. Once we got to the process of IDing them I think it was what I expected, difficult, but not impossible. The hardest thing is getting the pictures in the first place.

The ability to get those pictures has been greatly influenced by the advent of digital photography. Photo-ID on harbor porpoises just wouldn’t be feasible when all we had was film cameras. The amount of money to develop all the photographs, most of which would not be usable, would be prohibitive. We take a LOT of pictures that aren’t usable for photo-ID purposes. But with digital photography that doesn’t cost you anything. You can delete what you don’t want without paying a cent. Thus the combination of someone taking the time, with the right technology, is what was needed to show that this was feasible, and not as difficult as previously thought.

So, you could track these individuals. What did you find out about the animals in your study?

CE: We were so excited when we got our first photo-ID match! Not only was this exciting because we were showing that photo-ID could be used on this species, but also that an individual returned to our study area – meaning there might be more that show site fidelity to the area. And that is what we found. At least 35% of the individuals in our catalogue have been seen over days, weeks, months and years. Some individuals we have seen year-round, in every season. We have matches for individuals over at least 4 consecutive years and we still have backlogged photos to ID from the last 2 years, so that number will likely increase. What this means is that there might be a local population or community that uses this area and it is important for their survival.

What have you discovered so far regarding their social structure?

CE: This is a much trickier question to answer, and one we just don’t know about yet. This is one of the questions I am most interested in answering, as my past research is all about the social structures of the spotted and bottlenose dolphins in the Bahamas. The problem is first you have to have a lot of identified individuals – this we have a pretty good handle on at this point. Second, you need a lot of resightings of individuals – this is what we need more of. We have quite a few individuals with multiple sightings, but need more for this type of work. Lastly, we need to observe groups where all or most of the animals are identified – this is the trickiest part, especially with harbor porpoises. Their elusive behavior and small size makes getting photographs of everyone in a group very difficult. But we are on our way! We have seen a few individuals that seem to show up with certain other individuals on occasion, and time will tell what these relationships are and how they fit in the society as a whole. We just need to keep getting out there and getting those photos.

You went from being a research assistant and graduate student to running your own research nonprofit. What did you learn from your time at WDP that might’ve helped or prepared you to do that?

My work with WDP prepared me in many ways for my work here. Everything from the field work to the office work, as running a project involves a lot more than just field work. At WDP we all pitch in, from dishes and cleaning to data entry and field work. That mentality is vital for a small nonprofit, where we all have to wear many hats to keep the work going.

Doing photo-ID for 10 years with WDP on two different species that required different photo-ID techniques (spotting patterns for spotted dolphins, and nicks/notches for bottlenose dolphins; scars used for both species when present) gave me the skills and confidence to do this work on another, more difficult, species.

I learned a lot from Dr. Herzing about running a project, and what that entails. Working on the boat also teaches you how to work with a variety of different people in relatively confined spaces, when you are 40 miles from land on a 60ft boat, there is limited space! This is a critical skill for scientists as we rarely work on our own, and the ability to work with your colleagues is critical to continued success. I am so grateful for my time with WDP and all that I learned, I would not be where I am today without it.

Cindy Elliser, Ph.D., as a researcher with WDP collecting underwater behavioral data on bottlenose dolphins.

What is something you want people to know about harbor porpoises and your work?

That harbor porpoises are cool!! I joke, but not really. This species is too often overlooked as nondescript or boring. Many people in this region don’t even know they exist or think they are dolphins, even though they are the most common cetacean in the Salish Sea. Other species, like the killer whale, just overshadow them —and sometimes eat them. But just because an animal isn’t flashy, doesn’t mean they aren’t super interesting, you just have to take the time to look. We have learned so much about the harbor porpoise in the last seven years, and I think most people are surprised at how amazing these little animals are when I give educational talks. They are just as important to the ecosystem as killer whales, and we need to know more about them.

An individual in the PacMam study site known as Piano, first seen in 2017 and resighted in 2021.