We know a lot of you have followed our work for awhile now — some of you since the very beginning — and some of you have even been out with us on research expeditions. For the start of the new year, we’d like to provide a review of what we do and the dolphins we study, because there is a lot!

About Us

For starters, we’re a scientific research non-profit that was founded by our current research director, Denise Herzing, Ph.D. We study two species of dolphins that live on the Bahamas Banks — the Atlantic spotted dolphin (Stenella frontalis) and the Atlantic bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus).

Denise Herzing, Ph.D., founder and research director

Our goal is to gather long-term, non-invasive information on the natural history of these dolphins, including behaviors, social structure, communication, and habitat; and to report what we have learned to the scientific community and the general public.

We observe the animals from the surface and in the water, but the most important principle guiding our data collection effort is simple: IN THEIR WORLD, ON THEIR TERMS.

The Dolphins

As I mentioned before, we study two species of resident dolphins that live on the Bahamas Banks. During any given season, community size averages 100 Atlantic spotted dolphins and 100 Atlantic bottlenose dolphins in the study area.

The Atlantic spotted dolphins are the smaller of the two species and average about 5 to 7 feet in length.The spotted dolphins are born all gray and gain spots with age, until their spots begin to fuse and form more of a color pattern. But these spot patterns can actually help us guesstimate their age, if we don’t know exactly when they were born because they have distinct age classes based on their color patterns too. The four color phases are: two-tone (0-3 years), speckled (4-8 years), mottled (8 – 15 years), and fused (15 plus).

An Atlantic spotted dolphin mom with her all grey calf, who will gain spots with age.

The bottlenose dolphins average 10 to 14 feet and weigh over 1,000 pounds. They’re bigger! And while some adults can have some black spotting on their bellies, they are generally gray.

Two bottlenose dolphins.

The dolphins each live in a community of about 100 animals. But there are smaller groups, based on their social structure — who likes to hang out with who. These groups are always changing, coming together and breaking apart, which is called a fission -fusion society.

Typically, the female dolphins associate most with their other female family members and females within the same reproductive state. So, a mom with a calf spends time with other moms with calves. The teenage females who are rowdy, independent and playful all hang out together. The pregnant females hang with other pregnant females.

Zion, a pregnant female

For the males, they tend to form a best-friend for life, in what’s known as an alliance. Most of the times these are pairs, but occasionally they are a trio, like 3 males in our study population: Toad, Pulsar and Baelish. You will typically never seen one without the other. At times, the male pairs will meet up with other males to form coalitions. These alliances and coalitions serve them well during aggressive encounters with other spotted dolphins or bottlenose dolphins, but also to try and secure mating opportunities.

Both dolphins eat fish in the sand, though in different areas and on slightly different species. Bottlenose dolphins tend to dig deeper down into the sand for fattier fish, like conger eels. Additionally, the spotted dolphins also feed in deep water at night off the edge of the sandbank, for flying fish and squid. We’ve never observed the bottlenose doing this.

A female spotted dolphin chasing a flying fish in deep water at night. Photo by underwater/conservation photographer Nicodemo Ientile.

Why The Bahamas?

With clear, shallow water that’s relatively calm during the summer season – The Bahamas is the perfect place to study the underwater behavior of dolphins.

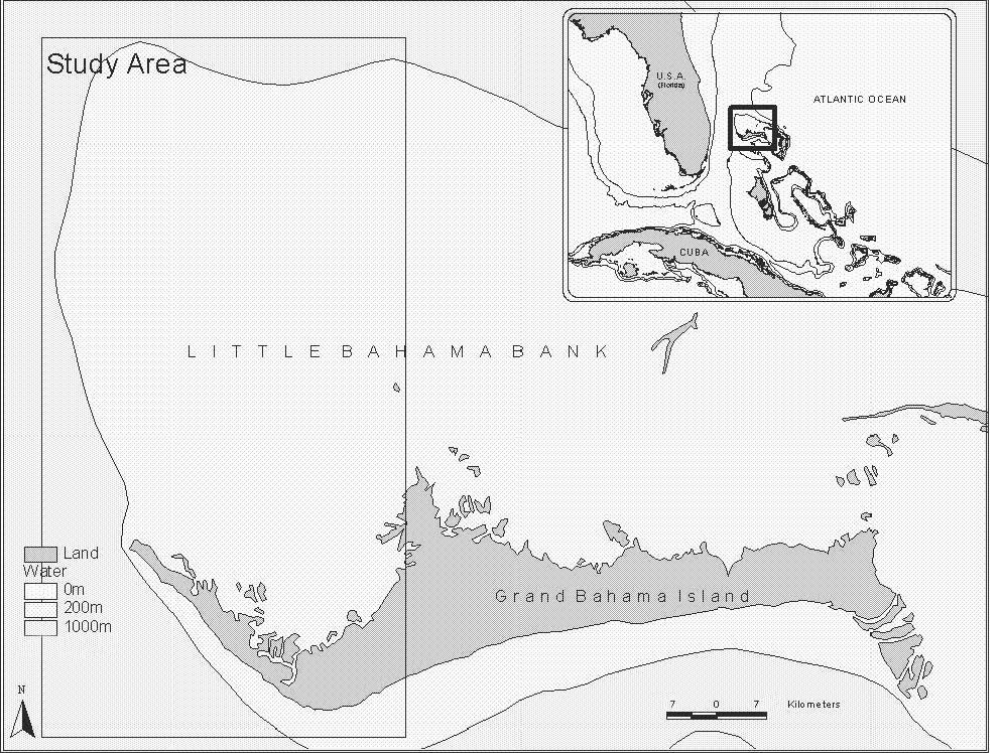

We work on the western edge of both Grand Bahama Island and Bimini. These sandbanks average in depth from about 20 feet to 50 feet, with average visibility of 30 feet (which again makes it great for underwater viewing of dolphin behavior!).

The two islands where we work – Grand Bahama Island and Bimini.

Zoomed in image of our field site off Grand Bahama Island.

How We do the Research

During the field season, WDP crew head over to the Bahamas on our 62-foot power catamaran, Stenella to live at sea and study the dolphins. We spend anywhere from a week to 10 days at sea before coming back to Florida to refuel and replenish provisions.

While in our study area, we anchor in a shallow protected area at night and pull anchor in the morning around 9:00am to start looking for dolphins. We spend a lot…..a lot…..of the day driving around searching for animals. There is a lot of down time, when people can rest, read, and get work done. One team member is always on ‘Dolphin Watch’ in hour-long shifts. Once someone sees dolphins, they stomp to let everyone inside know. Then, we start gearing up to get in the water to collect data in small teams of 4 or 5. As Denise often says, it’s a little like being a firefighter. It’s a lot of sitting around and waiting, then dolphins show up and it is go time!

Searching for dolphins – it always helps when seas are calm.

Our captain with the “Dolphin Watch” crew.

Our first mate and research assistant getting ready to enter the water.

The team going in the water puts on their masks, fins and snorkels. Researchers and interns grab video cameras, underwater cameras and fecal belts (to collect fecal samples for genetic analysis). While this is happening the topside crew are keeping an eye on the dolphins. When everyone is ready, the captain sets us up so we can slip into the water from the side of the boat with the dolphin group for an encounter.

Research assistant collecting underwater behavior and acoustic data.

Data collected on both species includes individual identification, age, sex, maternal relationships, social behaviors, and vocalizations. We also collect data on environmental conditions, like sea state, wave height, cloud cover, bottom type/habitat, and depth.

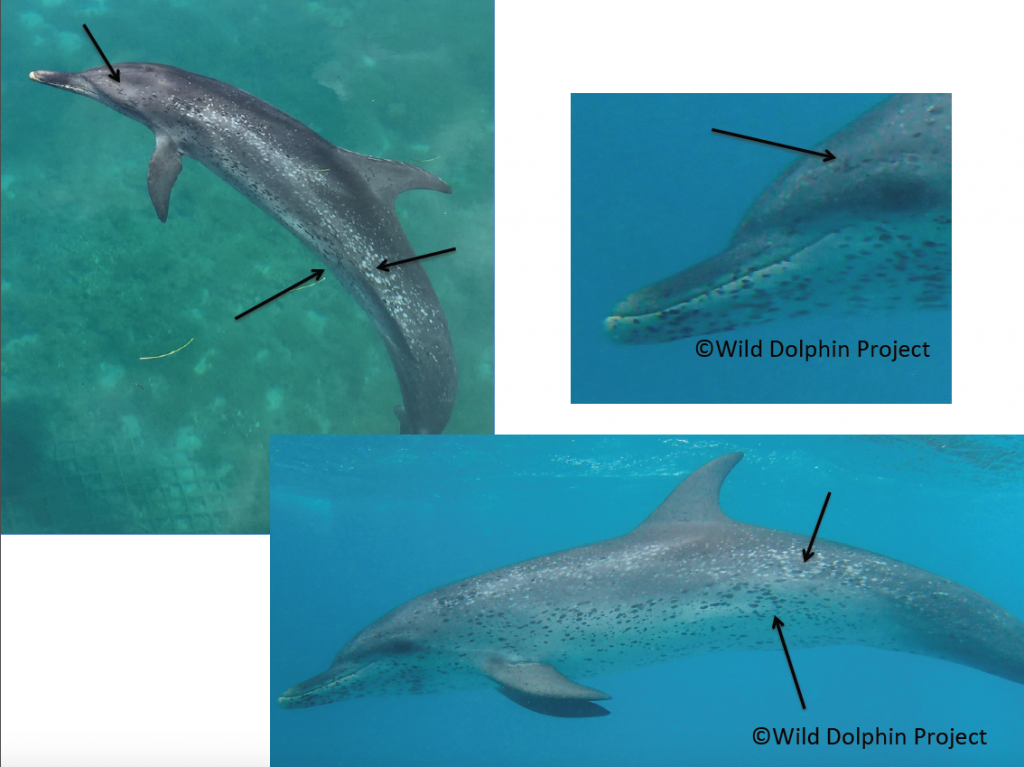

To identify individuals we use spot patterns as well as scars, and the nicks and notches out of flukes.

To identify the sex of an individual, we check their genital slits on their underside. A male will have one long slit and a little dot (the anus). A female will have a shorter slit, with two smaller slits on either side (think division sign), which are her mammary glands where calves nurse.

After we collect data, we enter it into our digital databases so that when we’re back at home during the off-season, we can pull the data for various research questions we are working on.

Research staff and interns entering data.

Adding Technology

In the last decade, we’ve expanded our use of technology to collect data and learn more than ever about these animals, including the use of drones, passive acoustic monitoring, underwater computers called CHAT (Cetacean Hearing and Telemetry) and an underwater sound localization device, called ASPOD, developed by our colleague and collaborator Matthias Hoffmaan Kuhnt, Ph.D.

Collaborator Matthias Hoffmann Kuhnt, Ph.D., with ASPOD, an underwater sound localization device.

The Crew

When we’re out at sea, it takes a team to make the research work. In addition to our research staff and research interns, we have a full-time captain and co-captain/first mate, as well as a cook (who often has the most important job on the boat of keeping us fed).

Dig Deeper

Interested in more about working with wild dolphins? Check out this blog with research assistant Cassie Rusche, as she discusses what it’s like to be a dolphin field biologist.

Interested in learning more about what it’s like to be a cook or captain on a research vessel? Check out these blogs:

Interested in learning about the differences in feeding behavior between spotteds and bottlenose? Check out this blog, Feeding Frenzy.