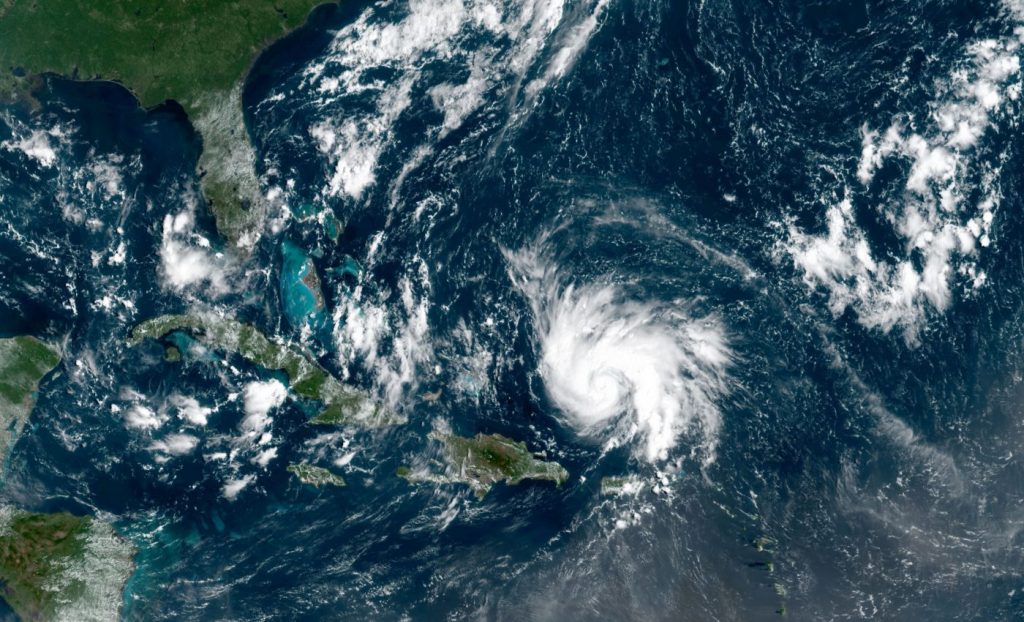

On September 1, Hurricane Dorian struck the Bahamas, including the Abacos and Grand Bahama Island. It was the first major hurricane of the 2019 season, with maximum sustained winds of 185 mph. We’re heartbroken for the people of the devastated islands who have lost their homes, jobs and loves ones. (Fortunately, we were able to raise $40,000 to bring supplies over with our research vessel).

But, what happens to dolphins during hurricanes?

Dr. Denise Herzing and the Wild Dolphin Project have been monitoring the resident dolphin community who live on the shallow sandbank of Grand Bahama Island since 1985. We’re all anxious to see how the dolphins fared after the storm, because it’s not first time a major hurricane has struck the area.

In 2004, Hurricanes Jeanne and Frances were two very strong cat 2/3 hurricanes that hit the Bahamas. Just like Dorian, Frances hovered over the Bahamas for days before heading toward Florida. Additionally, both Frances and Jeanne hit within a few weeks of each other. When we returned the following summer for our normal field season, about 30% of both the spotted and bottlenose communities were gone.

“Whether they left, or died, we cannot say for sure,” says Dr. Cindy Elliser, research director and founder of Pacific Mammal Research. Elliser was formerly a research assistant with the Wild Dolphin Project for 10 years. Part of her doctoral work was examining the social relationships of the dolphins and what happened to those relationships following the hurricanes. “Based on their history and residency I believe they died, if they had moved I would expect to have seen them in a neighboring community (in the Abacos, Bimini or even FL), and none of those lost dolphins have been sighted again. “

Cindy Elliser, PHD, research director and founder of Pacific Mammal Research and research associate with WDP.

So, why exactly would marine mammals equipped for a life at sea, die from hurricanes?

As mammals, dolphins must surface every few minutes to breathe. “Imagine having to swim in the middle of large waves, rain and massive wind, having to come to the surface in those conditions,” says Elliser. “If nothing else it would be exhausting. Some may have died in the roughness of the seas, or from exhaustion after.” Facing these conditions would be particularly challenging for new calves, which are often born in the fall and need to learn to swim, breathe and nurse.

Another possibility, says Elliser, is that the storms changed the availability of their food source or some aspect of the food web. Hurricanes kick up dirt and sand in shallow water, and this kills fish that essentially suffocate when their gills get clogged and the water is devoid of oxygen. Coral reefs and seagrasses also die when sunlight gets blocked by the stirred up water. “Since we did not see the animals until May (and the hurricanes were in Sept/Oct), we don’t know if it was an immediate loss, or a gradual one.”

Changed Relationships

The impacts from hurricanes on dolphins extends beyond the presumed deaths. As social mammals, it can change their relationships and behavior. Within the entire community of about 100 animals (this number varies year to year), the spotted dolphins have smaller groups, called clusters. These clusters are based on their geographic range within the study area, as well as social relationships. Within those clusters, individuals seemed to come together and interact more with all members of their cluster, rather than separating by sex, age, or preferred companions. “I think makes sense,” says Elliser. “You band together when some are lost. This is important for safety, as well as to continue the behaviors that are required for continued survival of the group, like mating and hunting.”

The bottlenose dolphins had a bit of a different story, says Elliser. They lost about 30 percent of their community, but had an influx of immigrants of about the same amount. And then, the community of individuals split into two smaller groups, comprised of both the original residents and new immigrants. We noticed little overlap between the two smaller groups, says Elliser. So, while the spotteds came together into a larger group, the bottlenose separated.

Lastly, after the hurricanes, even the relationship between the two species changed. The spotted and bottlenose dolphins regularly interact in the Bahamas and event fight. Following the 2004 hurricanes, we witnessed fewer mixed encounters. One particularly overt behavior — called side-mounting — that the bottlenose males use during aggressive fights with the spotteds wasn’t observed again until 2009. “It is likely that although these mixed species encounters are important for the ability to coexist on the sandbank together, so they continued, the focus of the encounters changed as each species had more pressing matters of stabilizing their own communities after such large demographic disturbance,” says Elliser.

After Dorian

As stated before, all of us at the Wild Dolphin Project are anxious to see the dolphins following Hurricane Dorian, who have become like family. We’ve watched them grow up and watched calves become mothers, or males that began as rambunctious youngsters turn into mature, strong males with alliances.

Dorian sat and hovered over the Bahamas, and was far more powerful than either Jeanne or Frances. “I just worry that they may have sustained even larger losses than before – which is compounded further in that 50% of the population moved to Bimini in recent years, which I guess is good for those animals, but that means there are even fewer dolphins left off Grand Bahama and large losses there could mean the end of that community,” says Elliser.

Dolphins are intelligent and adaptable. Like mentioned above, 50% of the community from Grand Bahama moved to a new island in 2013, likely due to a crash in the food web. Their adaptability will be the key to their survival in the coming years as they face threats from climate change and human activity.

Fortunately, on our relief trip we did find four of our dolphins on Little Bahama Bank off Grand Bahama Island. We found Amanda with her calf Astro, as well as two males, Poindexter and Navel.

“As more and more things are changing, and changing fast, the plasticity of a species will be critical in their survival. Luckily dolphins are good at this, so it bodes well for their future as a species,” says Elliser. “But at some point plasticity won’t be enough, and we need to make sure we don’t take things to a tipping point where we can’t come back.”

Read more about impacts of hurricanes on animals:

What do Hurricanes Mean For Dolphins

What happens to Fish and Other Sea Creatures Underwater During a Hurricane

When a hurricane hits, what happens to sharks, dolphins and marine life?