Trip 1: Diving Right Back In

After a long off-season on land, our team was excited to dust off their fins and make their way back to the clear blue waters of the Bahamas for the first trip of the field season. With some new crew on deck, we geared up for a successful trip and were eagerly awaiting to set sail on the Stenella. The Bahamas welcomed us with sunny skies and some rough seas (just to really make sure everyone got their sea legs quick!).

We spent the first couple days searching for the spotted dolphins on Little Bahama Bank. While searching, we explored a few great snorkel spots including Sugar Wreck. These beautiful sites were filled with lots of colorful fishes, sharks, and squid, but no dolphins. We then made our way down to Bimini and enjoyed an afternoon snorkel at Hesperus Wreck, but still no dolphins. Even with traveling to well known locations, we had little luck in sightings and were starting to wonder where these elusive dolphins had gone to.

Finally, on Day 5…bang bang bang! We heard the unmistakable foot stomping on the bridge that lets all of us know we have dolphins! The excitement was palpable, and everyone slid into their snorkel gear in preparation for our first encounter.

We were first met by Tyler and her second year calf Toggle, who already has spots developing on her body. For more on color phases, check out our blog on the Life Cycle of an Atlantic Spotted Dolphin. From then on, we had daily encounters with the spotted dolphins until it was time for us to depart across the Gulf Stream again. By the end, we observed lots of familiar faces including Moose and Destiny. These two juvenile males are almost always seen traveling and socializing together. This could be the foundation of a long-term association we often see in male spotted dolphins called an “alliance”, which can continue throughout their entire lives.

A juvenile spotted dolphin male Moose, always curious! Photo by RA Alexandra Rose.

We even had an encounter with a group of pregnant bottlenose dolphins and were able to observe them crater feeding. This is a common method of foraging accompanied by lots of clicks and buzzes, which we could hear clearly while in the water with them. Though we weren’t able to identify the individuals, most of them had very recognizable scars that will make them easy to identify in future sightings. We took lots of great photos that will allow us to keep track of these individuals through photo identification and better understand their life history. All in all, it was a successful first trip and a great start to the field season!

Bottlenose dolphin by Jake Prentice.

June Trip 2: Cetacean Surprise

Take 2 everyone! We couldn’t stay away for too long, and for the second time in June we crossed the Gulf Stream to return to the beautiful Bahamas. This time, we were accompanied by colleagues from all over the country, including the renowned Dr. Adam Pack from University of Hawai’i-Hilo.

After making our way to West End, we traveled down to Bimini and encountered a group of bottlenose dolphins on our second day there. Amidst the scanning and feeding, we recognized one of the bottlenose dolphins in the group as one seen on our previous trip. Just a few hours later, we sighted a group of 20 spotted dolphins including 4 mother and calf pairs. It is common for us to see females in similar reproductive stages traveling together. For instance, pregnant females will often travel with other pregnant females, and same goes for mothers with dependent calves. Two of the calves, Alfresco and Toggle, were first seen last season, so seeing them again this year is really exciting considering that calf mortality is 25% in their first year of life. These two are beating the odds and we hope to see more of them throughout the summer.

An Atlantic spotted dolphin calf, Toggle, playing with sargassum. Photo by RA Alexandra Rose.

On our last full day in Bimini, we witnessed something extremely special. While out in the deep water, we sighted a pod of false killer whales, Pseudorca crassidens, splashing in the distance. False killer whales live in semi-tropical and tropical waters, can grow up to 20 feet in length, and are known to prey on other cetacean species. We estimated there were over 10 individuals in the pod, including a curious calf who made close passes by the boat only to be redirected by an adult back to the main group.

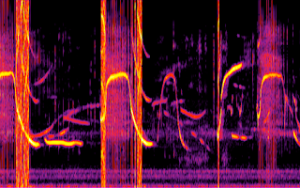

Their vocalizations were varied and loud enough to be heard in our hulls and at the surface. We lowered a hydrophone into the water attached to a sound recorder so we could further analyze the myriad of whistles and clicks that came from this chatty group. It wasn’t long before we discovered the cause of the initial splashing. A close pass by several of the whales revealed the large shark being dragged around, played with, and eaten. It was fascinating to witness such a raw moment in nature and observe their natural, undisturbed behavior. The experience rounded off another productive trip and left us counting down the days till we returned.

Surfacing false killer whale in deep water. Photo: Wild Dolphin Project.

Sample of spectrogram of false killer whale vocalizations.