Recently, WDP graduate student Brittini Hill completed her master’s degree and thesis research. So, WDP sat down with Brittini to talk to her about her research and why she was interested in this question. Check it out.

WDP: What was the goal of this research paper?

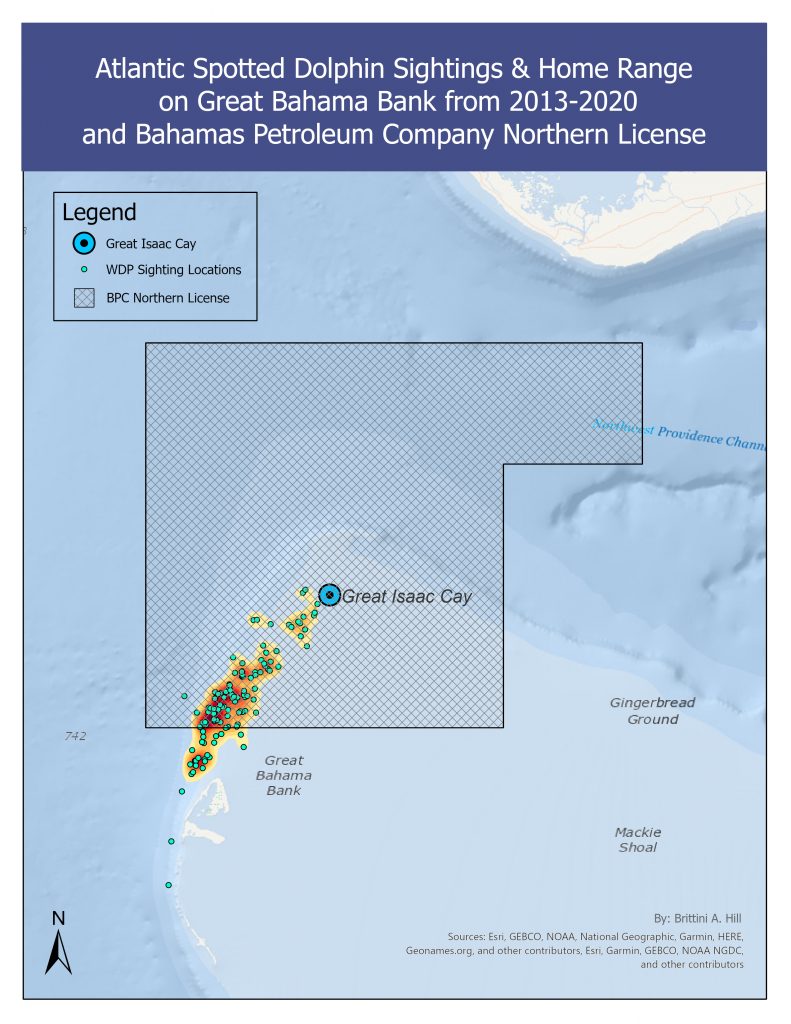

BH: In 2013, an unprecedented mass emigration event was observed by the WDP when over half of the resident Atlantic spotted dolphin community on Little Bahama Bank (off Grand Bahama Island) relocated 161km south to Grand Bahama Bank (off Bimini). The displacement followed significant decreases in sea surface temperature and chlorophyll a concentration, indicating a likely tipping point in prey availability driven by climate change. The goal of my master’s thesis was to determine if there were significant size differences in immigrant and resident dolphin home ranges and to compare behaviors and habitat characteristics for both the immigrant and resident dolphins.

WDP: Why were you interested in this question?

BH: As Earth’s species are being redistributed at increasing rates, this study provided a rare opportunity to focus on a species for which there is long-term data available for comparison before and after a home range shift into a new area where interspecies (meaning arising between species) and intraspecies (meaning between or among members of a single species) interactions may occur. To our knowledge, this is the first cetacean study of its kind to analyze changes in immigrant home range characteristics and use following a climate-driven displacement.

Understanding range size and how it changes through time is an important ecological and evolutionary characteristic of a species, and it is a priority in understanding vulnerability to local and global extinction. The results will help inform management and conservation decisions and further the understanding of climate-driven displacements in less studied species.

WDP: So, how did you do this research?

BH: First, I examined the home ranges of three communities of spotted dolphins: LBB residents on LBB from 2005-2012, LBB immigrants on GBB from 2013-2020, and GBB residents on GBB from 2013-2020. To do that, I used long-term data collected by the WDP and mapped the dolphin sighting locations using ArcGIS, a geographical information system. Then I used two programs, the Geospatial Modeling Environment & R, to run individual density-based home range models, which were mapped in ArcGIS.

The areas were calculated, and statistical analyses were run in R. At each sighting location, we also collect environmental and behavioral data. This allowed for the comparison of behavior frequencies and habitat characteristics between immigrant, resident, and mixed groups of dolphins.

WDP: What were the major results of your study?

BH: This study illustrated costs and benefits associated with emigration. For instance, immigrant dolphins maintained larger individual home ranges and core areas (areas of increased use within the home range) in what seemed to be overall lower quality habitat. Residents maintained access to prime habitat — shallower depths with sandy bottoms where primary prey items like lizardfish can be found. Immigrants’ larger ranges extended north beyond the boundaries of residents’, gaining the benefit of exclusive access to primary nocturnal feeding grounds at the cost of increased predation risks in deeper water. Immigrants’ ranges overlapped with residents’, and immigrants were more often found in mixed groups with the benefit of increased courtship behavior and mating opportunities.

However, in the presence of residents, immigrants faced a decrease in foraging opportunities and an increase in costly aggressive behaviors, which occurred more often than courtship. This supports the hypothesis that competition from residents has decreased immigrants’ access to prey, driving the requirement for larger immigrant home ranges and core areas. These findings illustrate that range shifts caused by a rapidly changing environment will be more complex than predictions based on climate variables alone, and non-climatic factors, such as the strong effects of local competition in novel areas, should be considered in conservation and management decisions.

Photo by Brittini showing interspecies aggression between Atlantic spotted dolphins on Grand Bahama Bank in the Bahamas.

WDP: Was anything about your results surprising or what you expected?

BH: When I began my master’s thesis, I set out to compare the home range sizes and characteristics of immigrant and resident dolphins. While I expected to get results, I was surprised by just how clear the findings were. For example, we had thirteen dolphins sighted twenty or more times on LBB as residents from 2005-2012 who then emigrated in 2013 and were sighted 20 or more times on GBB as immigrants from 2013-2020. Some of these individuals were Achilles, Littleprawn, Nassau, and Pointless. All thirteen dolphins maintained larger core areas as immigrants than as residents, and all but one individual maintained larger home ranges. The paired t-test statistical analysis revealed that individuals maintained significantly larger home ranges (34%) and core areas (94%) as immigrants than as residents.

WDP: So, now that we’ve talked about your actual study. What was the hardest part about this research and/or being a graduate school in general?

BH: For me, the most time-consuming part of this research was learning to use new computer software. I had experience with R in my undergraduate classes and research, but I had never used ArcGIS or the Geospatial Modeling Environment. It took months of troubleshooting and a lot of help from my university’s Geography department to get my home range models running properly. While this was the hardest part of my research, it was also the most rewarding. I learned just how powerful these tools are in analyzing the data we collect in the field to answer important biological questions.

WDP: Same question as above but reverse- what was the best part of the research and/or being a graduate student.

BH: I had two favorite parts of being a graduate student. The best part was the field work. I absolutely love being a part of the WDP summer field team, observing wild dolphins in their natural environment and learning about their behavior and lives. My second favorite part was sharing my work with others. In graduate school, there are a lot of opportunities to present your research, not only to your department, but to broader audiences as well. I am passionate about sharing my work with people outside of the scientific community to inspire a love and understanding of Atlantic spotted dolphins, the oceans, and conservation. People won’t fight to protect what they don’t know and love.

Brittini in the field collecting data.

Brittini (far right) in the field with other researchers and crew

WDP: So, having said that. What would you want someone to take away from your research — what’s the big picture?

BH: Our blue planet is facing great losses of biodiversity, the variety of life forms on Earth. Due to climate change, species are faced with many challenges to which they must adapt or cease to thrive. As we saw with the climate-driven mass emigration of spotted dolphins in the Bahamas, the immigrant dolphins are dealing with many cost to, like maintaining larger home ranges in lower quality habitat while facing decreased foraging and increased aggression. During my research, the Bahamas Petroleum Company was granted exploratory oil drilling permits in the heart of our dolphins’ home range. As advocated for by many, including Sylvia Earle and David Attenborough, we need more marine (and terrestrial) protected areas for wildlife to recover from the many stressors they face.

WDP: You were a graduate student and also a mom, which I know was probably challenging at times. So, for anyone else out there that may be thinking about graduate school with a family, what would you want them to know?

In the United States, about two-thirds of mothers with children under 18 work full time. I am among the majority of moms who balance motherhood and a career. I became a mom in 2015 and started working with the WDP in 2018. For the first three years of my son’s life, I primarily stayed at home with him, teaching a few local yoga classes each week. But as he got older and was no longer nursing, I felt ready to jump back in and pursue my master’s degree. When weighing the costs and the benefits of spending time away from my son and conducting research for my master’s thesis, I came to understand that my son, who had by this time developed secure attachment, needed more than just my constant presence. It is important for me to set an example of being dedicated to your family and to meaningful work. I am both a mother and a scientist, and one identity is not exclusive from the other.

While society puts a lot of pressure and shame on mothers to do all and be all for their children, it truly takes a village to raise a child right. I am lucky to have a supportive spouse and extended family who step in to be an integral part son’s care while I am out at sea. When I am at home with my son, I focus on being present and having quality time with him. We have conversations about my work and his feelings — we keep things open. I engage and involve him in any way that I can. During our three years in Colorado, we volunteered with the parks and wildlife’s raptor monitoring team and did weekly park and river cleanups. Almost every day, we hiked and took pictures of local wildlife. Even at a young age, my son understands the importance of our lifestyle choices on animals and the environment, and he loves to tell people about protecting animals. As he gets older, I cannot wait to get him more involved in my work.

For any mothers wanting to go to graduate school and do field work, do not be discouraged. With a supportive team of family or friends around you and a lot of hard work, it is possible. Remain flexible and be willing to work late nights after bedtime stories. Don’t feel like you have to do it all alone, and don’t be afraid to ask for help when you need it. Your children will be better off for seeing your dedication and passion to the things that you love. We are fighting for the planet that we will leave to our kids. Who better to be a part of this fight than mothers?

Brittini with her family in Colorado